Why the 1950s?

Gary K. Wolfe

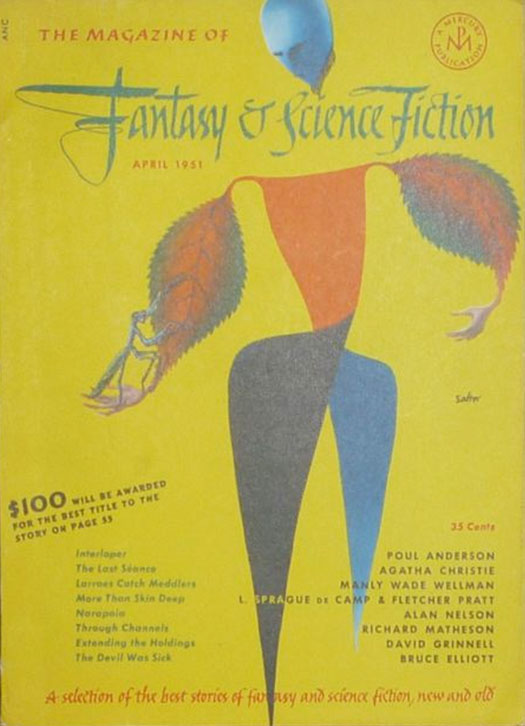

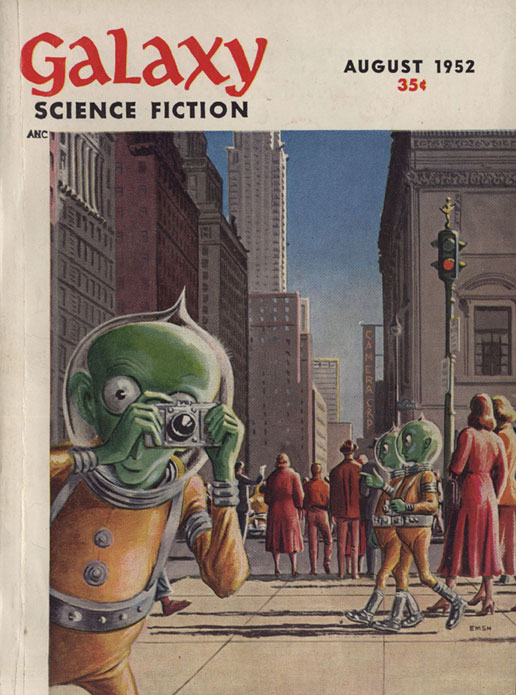

Golden Ages are as much a matter of nostalgia as of literary history, and Robert Silverberg, in a 2010 essay, persuasively argued that the Campbell “Golden Age” of the 1940s was a kind of “false dawn.” “The disruptions of the Second World War scattered Campbell’s talented crew far and wide,” he noted, and by the time they returned after the war Astounding had already begun to lose much of its luster—thanks in part to Campbell’s own growing fascination with fringe science ideas and L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics. A new generation of writers, not quite old enough for Campbell’s Golden Age, had come of age in the meantime, often working with editors other than Campbell. These writers included James Blish, Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, Damon Knight, Frederik Pohl, C. M. Kornbluth, William Tenn, Ray Bradbury, Alfred Bester, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Philip José Farmer, and many others. New magazines like Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction were more amenable to literary or satirical forms of science fiction than Campbell had been.

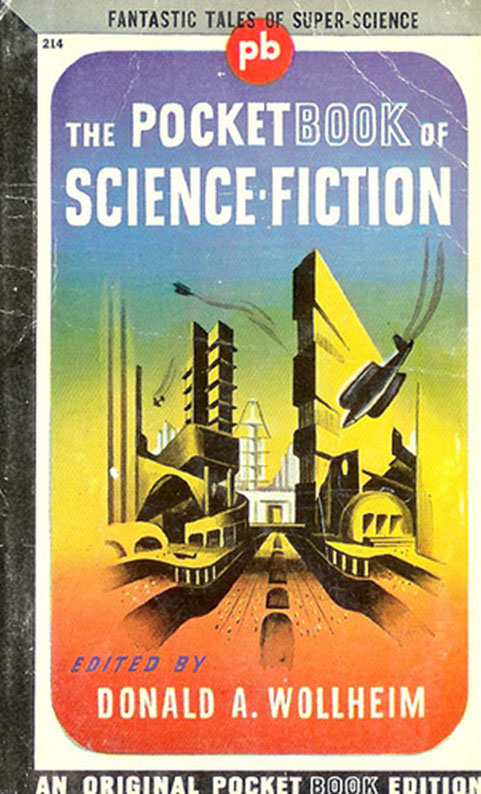

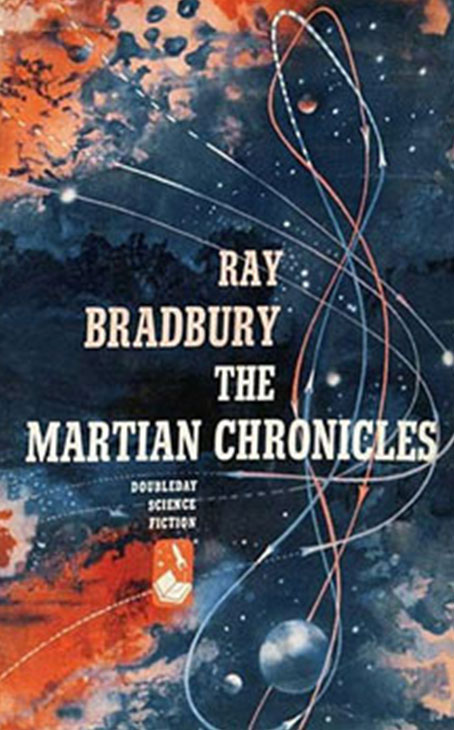

Equally important, the publishing environment had begun to change radically. The once-dominant pulp magazines were increasingly under siege from television and the burgeoning paperback book market, which had discovered science fiction as long ago as 1943, when Donald A. Wollheim’s anthology The Pocket Book of Science Fiction became possibly the first American book to use “science fiction” as part of its title. More important, major publishers such as Doubleday, Crown, Simon and Schuster, and Random House began publishing science fiction anthologies, and some began programs of original novels as well. “Until the decade of the fifties,” Silverberg writes, “there was essentially no market for science fiction books at all”; the audience supported only a few special interest small presses. Many of the early “novels” in this publishing boom were actually linked collections of previously published stories, such as Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy (1951–53), Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1950), Clifford D. Simak’s City (1952), A. E. van Vogt’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950), or Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth (1950). (Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human was developed from the novella “Baby Is Three,” but fully two-thirds of the text was written specifically for the novel.) Now there was a powerful emerging market for science fiction novels as novels: 1950 alone saw the publication of Isaac Asimov’s Pebble in the Sky, Robert A. Heinlein’s Farmer in the Sky, Judith Merril’s Shadow on the Hearth, and Theodore Sturgeon’s The Dreaming Jewels. By September of that year the New York Times could report that “more science fiction novels and anthologies will be published this fall alone than in any previous full year.”

It’s no surprise that Silverberg—whose own distinguished career as a science fiction writer began in the 1950s—should conclude that the 1950s was “the real Golden Age,” which saw “a spectacular outpouring of stories and novels that quickly surpassed both in quantity and quality the considerable achievement of the Campbellian golden age.” Not only was the short fiction of this era more diverse and ambitious than almost anything seen before, but for once it was realistic for a science fiction writer to think in terms of the extended, unified narrative that the novel as a form permitted.

Gary Wolfe