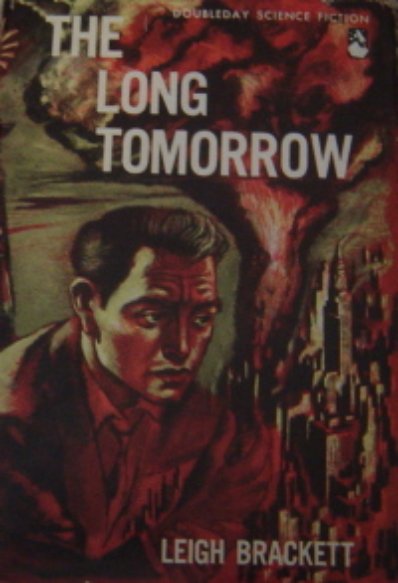

Nicola Griffith on The Long Tomorrow

Still Here

I read The Long Tomorrow for the first time in 2005. Five pages in, I wondered why I'd never heard of it. Twenty pages later, I couldn't understand why it wasn't universally acknowledged as a Great American SF Novel.

The opening of The Long Tomorrow reads like a King James Bible for the American myth: sure, rhythmic, and implacable. Brackett sets up her major theme in the first sentence: knowledge is sin, and fourteen-year-old Len Colter is about to take the step that will lead to his loss of Eden.

This is the theme of the Bildungsroman: loss of innocence, change, and the journey from safety into the unknown in pursuit of knowledge. But because Brackett's ambition was huge, she chose for her setting a post-nuclear Ruined Earth. She aimed for no less than the first serious science fiction novel of character.

In mid-century North America, I doubt there was any writer better equipped for the challenge.

Before Brackett wrote The Long Tomorrow (1955) she was expert in two disparate traditions: swashbuckling planetary romance (for the sf pulps) and hard-boiled crime narrative (a novel, and several screenplays including The Big Sleep). In 1949 she mixed aspects of these previously immiscible traditions––the grit and noirish interiority of hard-boiled fiction with an elegiac Mars dreaming of long-forgotten technology. The result was The Sword of Rhiannon, an exotic planetary romance cabled with gristle. But Rhiannon fails as a novel: the hero doesn't grow and change.

So Brackett tried again with The Long Tomorrow and this time she chose a landscape that Huck Finn might recognize (though peopled, it must be noted, almost entirely by white characters). Into a substrate composed of tropes familiar to any reader of the Great American Novel––the young hero seeking his place in the world, a pastoral America certain in its faith––she poured a healthy dose of sfnal anti-anti-intellectualism and, perhaps inevitably, the refusal of the hero's expected return to his beginnings.

The first third of the novel is masterful. Len is steeped in his culture. That culture's faith-based leadership plus its constitutional prohibition against cities makes clear how law can lead to taboo. Any proscribed activity requires pariahs, in this case the technological elite of Bartorstown. The forbidden fascinates the young. We watch, helpless, the inevitable fall from grace of Len and his friend Esau, and the beginning of their long journey to self-acceptance and belonging.

Brackett, however, was a product of her age. While the religion is beautifully handled––belief in a variety of sects, held with varying depth of feeling––it is entirely Christian, white, and run by and for men. She gives only men the agency to struggle and rebel against their constraints.

With that caveat, she handles the antagonism of science and religion adroitly. She melds the classic noir cri de coeur, "Why me?", with Len's sfnal anti-anti-intellectual crisis: "Oh God, you make the ones like Brother James who never question, and you make the ones like Esau who never believe, and why do you have to make the in-between ones like me?" In an even more impressive feat, she uses what would be a literary novel's denouement, Len's realization that faith is just another word for fear, to disguise a classic sfnal move: a vertiginous focus pull in which he understands that he is nothing, a speck, immaterial to continuing existence of the world.

It's fascinating to watch Brackett lay out her chainsaws and clubs and flaming torches and add them, one by one, to the bravura performance. Every now and again she falters––in the third section, when she has the most in the air, her voice wobbles, her characters lose definition, and this reader at least doubts the sustainability of Bartorstown's mission––but then she drives a brilliant spike through the confusion and pins us to the moment. I defy any reader to watch Joan walk through that doorway in her red dress and not be right there inside Len's skin, feeling him swallow and his world turn, just as it did on page one.

In the 1950s, this book must have turned its readers inside out like a sock. It wouldn't surprise me to discover it was a formative influence on the young Carl Sagan, the seed of Saganism: the notion that spacefaring nations would be rare because they would tend towards destruction before they escaped the gravity of their planet.

In the twenty-first century, we suspect that this may not be true. And we have writers like Leigh Brackett to thank.

Leigh Brackett

Nicola Griffith on The Long Tomorrow

Read Biography

Experiences as a Writer

Leigh Brackett looks back at her long and varied literary career in this 1975 interview, conducted at her home in Kinsman, Ohio, just a few years before her death.Audio: Leigh Brackett—An Audio Interview

Film critic Tony Macklin visited Leigh Brackett on a hot, humid, blazing July 1975 day at her farm house in Kinsman, Ohio. I vividly remember Leighs making us lemonade to help cool us—it was pure sugar.Other Novels by Leigh Brackett

Credit: Jennifer Durham

Credit: Jennifer Durham