Historical Context

Gary K. Wolfe

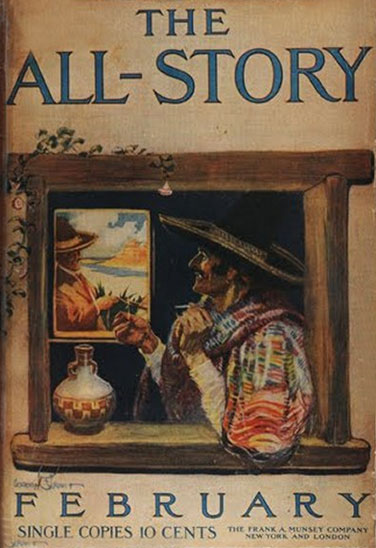

Science fiction was far from unknown in nineteenth-century American literature, but it wasn’t called that. As H. Bruce Franklin showed in his 1966 anthology Future Perfect: American Science Fiction of the Nineteenth Century, we can find examples of it in the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Ambrose Bierce, and others, and subsequent scholars have unearthed even more examples, including some of the “dime novels” that became widely popular in the 1860s and 1870s. But it wasn’t until late in the century that science fiction would begin to coalesce into an identifiable “story type” in the pages of the pulp magazines that followed on the success of Frank Munsey’s Argosy in 1896. By the early twentieth century, the pulps—so-called because of the cheap, acidic wood-pulp paper they were printed on—had begun to serialize popular adventure novels by H. Rider Haggard and others, soon developing homegrown writers such as Edgar Rice Burroughs (whose Under the Moons of Mars was serialized in All-Story in 1912, later retitled A Princess of Mars in book form) and A. Merritt (whose first fantasy story appeared in the same magazine in 1917).

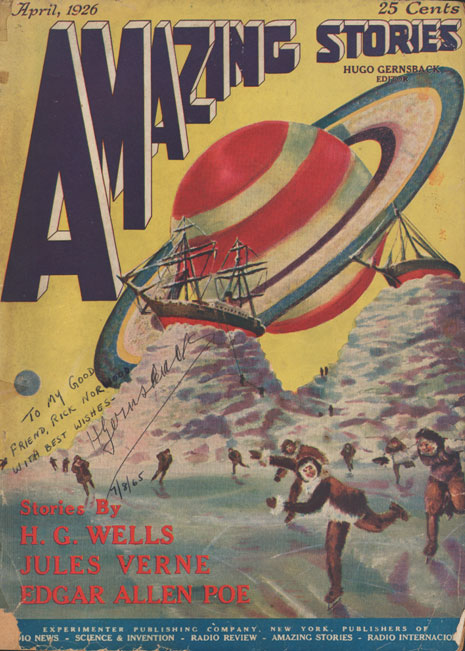

Meanwhile, Luxembourg immigrant Hugo Gernsback had begun a series of electrical-hobbyist magazines which sometimes featured stories we would now recognize as science fiction, including his own clumsily written short novel Ralph 124C 41+ in Modern Electrics in 1911. Finding the stories popular, he launched a magazine devoted to what he called “scientifiction” in 1926, titled Amazing Stories. Although Weird Tales, founded three years earlier, featured some science fiction among its supernatural horror tales, 1926 has become the date of convenience for literary historians seeking to trace the beginning of science fiction as a popular genre, or at least as a specialized market with a targeted readership. At first, Amazing Stories seemed determined to provide a primer for readers; the first half-dozen issues prominently featured the names of H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allan Poe on the covers, reprinting classic tales, although the famously garish cover paintings by Frank R. Paul probably did as much to call attention to the magazine on newsstands—and to give rise to the popular image of the pulps as tawdry and sensational. This image was not entirely inaccurate during the next decade of the “pulp era,” with its huge-scale galactic adventures and star-smashing weaponry in the work of E. E. “Doc” Smith, Edmond Hamilton, and others.

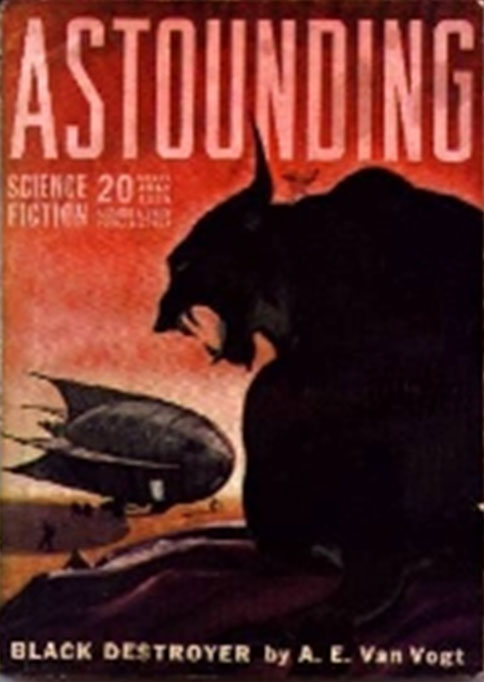

One of the authors of those early “space operas” was John W. Campbell, Jr., who clearly had a different vision for the genre, and set about implementing it when he was hired as editor of the pulp Astounding Stories in 1937. In 1938 Campbell changed the title to Astounding Science-Fiction, and by 1939 had begun to publish stories by a new generation of writers, including Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, and Isaac Asimov. Championing a science fiction based more on ideas than pure adventure, Campbell demanded that his writers learn the science they were writing about, and that the social and political implications of scientific innovations should be treated in a credible and realistic manner. He showered writers with ideas and interrogations that eventually shaped a new paradigm for the genre. This is why, both among older fans and popular genre historians, the early years of Campbell’s editorship are habitually referred to as the “Golden Age” of American science fiction. But was it the real, or the only, such Golden Age?