“Who?”: The Original Short Story

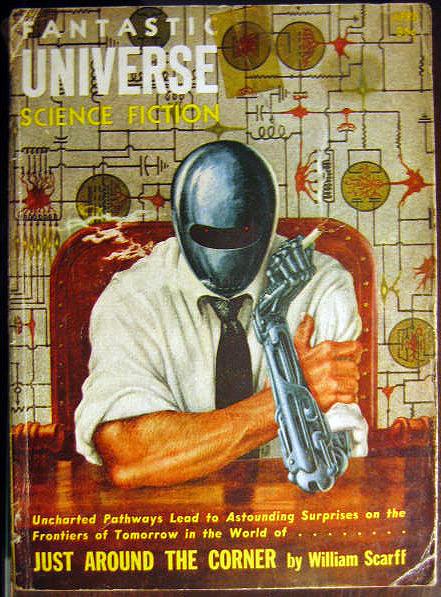

Like more than a few of the 1950s’ classic science fiction novels, Algis Budrys’s Who? began as a short story. He wrote it—he later claimed—having been inspired by a Kelly Freas painting he had seen in the offices of Fantastic Universe, and published it in that magazine in April 1955. Here is the original “Who?”

The concrete room was stifling in its smallness. Rogers had turned off the rattling air conditioners in order to keep the discussion below the level of a shout. The other men were sweating and mopping their faces, blinking their eyes against the sting of perspiration. But so was Rogers, and as it was his office no one protested.

Rogers looked around at them all.

“Well?”

They all looked at Barrister. Rogers could have meant any one of them, or all of them in general. But, in any group, Barrister was the one who spoke first.

He took the bit of his pipe out of his teeth and shook his head. “I don’t know. I’m running tests. I’ll have no results, one way or the other, for at least a week. That’s the best I can do.”

Finchley, next to him, was wordier. “How do you get at somebody like that?” He looked around at the other men and gestured helplessly. “He’s like a big egg. You can look at him all day. You can try to get inside him. Half your instruments are no good. You can’t even get an electrocardiogram. Any electrical equipment isn’t worth a damn on him.” He dropped his voice as though apologizing. “It hurts him if you try. He screams.”

Rogers grimaced, distastefully. “But he is Martini?”

Bowen shrugged. “What fingerprints he has, check out. If he isn’t Martini, he’s got five of his fingers.

Rogers slammed his fist against the top of his desk. “What the hell are we going to do!”

“Get a can opener,” Willis suggested.

“Look at this,” Finchley said. He touched a switch, and the film projector hummed as the room lights automatically went dim.

“Overhead pickup,” Finchley explained. “Infra-red lighting. We believe he can’t see it. We think he was asleep.”

Martini––Rogers called him that against his better judgment––was lying on his bed. The larger crescent in his metal skull was shuttered from the inside. The smaller one was open. The impression created was that of a man with eyes shut, breathing through his mouth. Rogers forcibly reminded himself that it was just an impression: that this was not necessarily the case at all, that it might not even be Martini. How could anyone be sure?

“This was taken at about two in the morning, today,” Finchley said. “He’d been lying there for a little over an hour and a half. I wish to God he’d breathe!”

Rogers frowned. All right, it was uncanny, not even having a respiratory rhythm to tell you whether the man was asleep or not. But he didn’t like Finchley’s being so upset about it.

A cue spot flickered on the film.

“All right,” Finchley said, “now listen.” The little speaker beside the screen crackled.

Martini began to thrash on his bed, his metal arm striking sparks from the concrete wall as it was flung about.

Rogers winced.

Abruptly, Martini began to babble in his sleep. The words poured out, each syllable distinct, the voice harsh, but the words twice as fast as normal.

“Name! Name! Name!

“Name Lucas Martini, born Bridgeton, New Jersey, May 10, 1938.

“Name! Name! Detail!… Halt!

“Name Lucas Martini, born Bridgeton, New Jersey, May 10, 1938 about… face! Forward… march!”

Rogers turned to Finchley. “Think they were walking him?”

Finchley shrugged. “If that’s a genuine nightmare, and if that’s Martini, then, yes, it sounds very much like they were walking him back and forth in a small room and firing questions at him. Keep ’em on their feet, keep ’em moving, keep asking questions, change interrogation teams every four hours, don’t let ’em sleep. You know their technique.”

“If that’s really Martini.”

“Yeah.”

“If it’s really Martini, I said.”

“I heard you.”

A man named Lucas Martini had been chief of research at the Mare Imbrium technical development center. One day the bubble housing on the center had blown––from the inside. A medical team from the Soviet sector had gotten there first.

It had been three days before Washington realized that Martini was unaccounted for. It had been a month before Moscow released the information that Martini was indeed still in one of their hospitals, undergoing “extensive treatment.” Unfortunately, the hospital was located in a military zone, and no Western doctors could be permitted to examine him. Nor was examination necessary. While Martini could not be moved, he was responding well to treatment by “teams of excellent specialists.” When he was convalescent, the government of the People’s Democracies would be happy to restore him to the brother democracies of the West.

It had been four months, despite the heaviest possible pressure, before Lucas Martini was declared convalescent.

What made it a tricky situation was the fact that Lucas Martini had been carrying the plans of the new K–88 in his head.

And the head of the man who was eventually returned––who might even be Martini––together with a number of other critical organs, was no longer of flesh and bone. It was metal.

“All right, Mike, what’s the breakdown?” Rogers sighed.

Barrister laid the first sheet down on Rogers’ desk.

“This is what his head works like––we think. It’s a tough proposition, not being able to X-ray.”

Rogers looked down at the mark-up sketch and grunted. Barrister took the pipe out of his mouth and began pointing out specific details, using the pipestem to tap the drawing at the indicated places.

“That’s his eye assembly. He’s got binocular vision, with servo-motored focusing and tracking. The motors run off that miniature pile in his chest cavity, just like the rest of his mechanical components. It’s interesting to note that he’s got a complete selection of filters for his eye lenses. They did the job up brown. By the way, he can see by infra-red.”

Rogers spat a shred of cigarette tobacco off his lip. “That’s interesting.”

Barrister grunted. “Now––right here, on each side of the eye assembly, is an acoustical pickup. Those are his ears. They must have felt it was better design to include both functions in that one central skull opening. It’s directional, but not so good as God intended. Here’s something else; that shutter is tough––armored to protect his eyes. Result: he’s deaf when his eyes are closed. Probably sleeps more restfully for it.”

“When he isn’t faking nightmares, yeah.”

“Or having them.” Barrister shrugged. “Not my department.”

Rogers nodded agreement with an expression indicating that he wished it wasn’t his, either. “What about his mouth?”

“The jaws and saliva ducts are mechanical. The tongue isn’t. The inside of the mouth is plastic-lined––teflon, probably, or one of its kin. My boys are having a tough time analyzing it. He’s pretty cooperative about letting us chip off samples.”

Rogers swallowed uncertainly. His nervous stomach was keeping him near the edge of nausea almost constantly. “Okay––fine,” he said in a brusque attempt to cover up, “but how’s all this hooked to his brain?”

Barrister shook his head. “I don’t know. He’s cooperative, but I’m not the boy to start disassembling any of this––we might not be able to put him back together again. All I know is that somewhere, behind all this hardware, there’s a human brain inside that skull. How it controls the mechanical functions of its body, I don’t know. The Russians have a good head start on us there. They’ve been monkeying about with this kind of stuff since before and during World War II.”

He laid another sheet atop the first, paying no attention to the pallor of Rogers’ face. His chief’s physiological reflexes weren’t his department either.

“Here’s his powerplant. It’s located where his lungs used to be, next to the blower that lets him talk and the most ingenious oxygen circulator I’ve ever seen. The power’s electrical, of course, tapping off a fairly ordinary small pile. It runs his arm, his jaws, his audiovisual equipment, the blower, and the blood oxygenation system.”

“How well is it shielded?”

Barrister let a measured amount of professional admiration show in his voice. “Well enough so we can X-ray around it. There’s some leakage. He’ll die in about fifteen years.”

Rogers grunted.

“Well, look, man,” Barrister pointed out, “if they cared whether he lived or died, they’d have supplied us with blueprints.”

Rogers caught him with a glance. “They must have cared at one time––they put in enough effort keeping him alive. And fifteen years might be long enough for them, if this isn’t Martini.”

Rogers looked at Bowen, and both of them shrugged hopelessly at the same time. “All right,” Rogers said, “the technical staff is showing slow progress, but that’s not our main problem. Let’s go down and talk to him again.”

Bowen nodded bleakly. He was attached to Rogers’ staff, but his training and primary obligations were FBI. So far, his reports had mostly consisted of short words surrounding long absences of significant information.

But he and Rogers had talked to Martini before. Aside from the fact that it was a disquieting experience, it was also, thus far, an unrewarding one. Martini wasn’t much help in explaining himself.

Martini’s room was as small as all the others in the Project. Rogers and his team had been fired up to the Moon in a hurry. The only available facilities had never been designed with this sort of operation in mind.

But then, Rogers thought with a touch of bitterness, what facilities had? Just as they’d jury-rigged their testing equipment, so they were jury-rigging their methods, devising their rules as they went along.

Only they weren’t going anywhere.

“Now, Mr. Martini,” Bowen was saying politely. “I know I’ve asked you before, but have you remembered anything since our last talk?”

The overhead light winked on polished metal. It was only after a second or two that Rogers realized Martini had shaken his head.

“No,” Martini said. “Not a thing. I remember being caught in the original blast––it looked like it was coming straight at my face and chest.” He barked a throaty, savage laugh. “I guess it was. I woke up in their hospital and put one hand up to my head.” His right arm––the fleshly one––went up to his hard cheek as though to help him remember. It jerked back down abruptly, almost in shock, as though that were exactly what happened.

“Uh-huh,” Bowen said quickly. “Then what?”

“After a couple of days, they shot a needle full of some anesthetic into my spine. When I woke up again, I had this arm.”

The motorized limb flashed up, and his knuckles rang faintly against his skull. Either from the conducted sound or the memory of that first shocked moment, Martini winced visibly.

His face fascinated Rogers. The two lenses of his eyes, collecting light from all over the room, glinted darkly in their recess. The grilled shutter which set flush in his mouth when he wasn’t eating looked like a row of dark teeth bared in a desperate grimace.

Of course, behind that facade, a man who wasn’t Martini might be smiling in thin laughter at the team’s efforts to crack past the armor.

“Lucas,” Rogers said softly, fogging the verbal pitch low and inside.

Martini’s head turned toward him without a second’s hesitation.

Ball one.

“Yes, Mr. Rogers?” If he’d been trained, he’d been well trained.

“Did they interrogate you very extensively?”

Martini nodded. “Of course, I don’t know what you’d consider extensive, in a case like this. But I was up and around after two months. They were able to talk to me for several weeks before that. In all, I’d say they spent about six weeks trying to get me to tell them something they didn’t know.”

“Something about the K–88, you mean?”

Martini shook his head. “I didn’t mention the K–88. I don’t think they knew about it. They just asked general questions: what lines of investigation we were pursuing, things like that.”

Ball two.

“Well, look, Mr. Martini,” Bowen said, drawing the man’s attention, “they went to a lot of trouble with you. Frankly, if we’d gotten to you first, there’s a chance you might be alive today, but you wouldn’t like yourself very much.”

Martini’s metal arm twitched sharply against the edge of the desk. There was an over-long silence. Rogers half-expected some bitter answer from the man.

“Yes, I see what you mean,” Martini said with shocking detachment. “They wouldn’t have done it if they hadn’t expected some pretty positive return on their investment.”

Bowen looked helplessly at Rogers. Then he shrugged. “I guess you’ve said it about as specifically as possible,” he told Martini frankly.

“They didn’t get it, Mr. Bowen,” Martini said. “Maybe because they outdid themselves. It’s pretty tough to crack a man who doesn’t show his nerves.”

A home run, over the centerfield bleachers and still rising when last seen.

Rogers pushed his chair back with a scrape against the concrete floor. “I think that’s all for today, Mr. Martini. We’ll be in to see you again, I’m afraid.”

Martini nodded. “I understand. But it’s all right with me. The quicker you get through with me, the faster I can get back on the job.” He flexed his metal arm, his hand rotating through 360 degrees at the wrist. “Ought to be able to pull some pretty fancy stunts with this, don’t you think?”

Rogers bit his lip. “I’m afraid that’s not going to be for quite a while, Mr. Martini.” He gestured lamely. “I’m sorry.”

Martini looked quickly from him to Bowen’s guilty face and back again. Rogers could have sworn his eyes glowed with a light of their own.

There was a splintering crack and Rogers stared incredulously at the edge of the desk where Martini’s hand had closed on it, convulsively.

“I’m not going back, am I?” the man demanded.

He pushed himself away from the desk and stood as though his muscles, too, had been replaced by cables under tension.

Rogers shook his head. “I couldn’t say, definitely.”

“But you don’t think so.” Martini paced three steps toward the end of the room, spun, and paced back. “They’ve washed out the K–88 program, haven’t they?”

“I’m afraid so.” He found himself apologizing to the man. “They couldn’t take the risk. They’re probably trying some alternate approach to the problem K–88 was supposed to handle.”

Martini slapped his thigh.

“Probably that monstrosity of Besser’s,” he muttered. He sat down abruptly, facing away from them. His hand fumbled at his shirt pocket and he pushed the end of a cigarette through his mouth grille. A motor whined, and the soft-rubber inner gasket closed around it. He lit the cigarette with hasty motions of his good arm.

“Damn it,” he muttered savagely, “K–88 was the answer. They’ll go broke trying to make that thing of Besser’s work.” He took a savage drag on the cigarette.

Abruptly, he spun his head around and looked squarely at Rogers. “What the hell are you staring at? I’ve got a throat and a tongue. Why shouldn’t I smoke?”

“We know that, Mr. Martini,” Bowen said gently.

Martini’s red gaze shifted. “You just think you do,” he said in a throttled voice. He turned back to face the wall. “You said you were through for today,” he said.

Rogers nodded silently before he spoke. “Yes. Yes, we were, Mr. Martini. We’ll be going. Sorry.”

“All right.” He sat without speaking until they were almost out the door. Then he said: “Can you get me some lens tissues?”

“I’ll send some in right away,” Rogers said. He closed the door. “I guess his eyes must get dirty, at that,” he commented to Bowen.

The FBI man nodded absently, walking along the hall beside him.

“That was quite a show he put on,” Rogers said uncomfortably. “If he is Martini, I don’t blame him.”

Bowen grimaced. “And if he isn’t, I don’t blame him either.” His brow was still furrowed in concentration. Finally he turned to Bowen. “Say, remember that Russian leader––whatzizname, back during World War II?”

Rogers nodded. “Uh-huh, Stalin. Why?”

Bowen nodded rapidly. “That’s it. I was trying to remember it. Read something about it, once. Know what ‘Stalin’ means, in Russian?”

Rogers shook his head. “No. What?”

“Man of steel.”

Rogers looked dully at Willis, the psychologist. It was early in the morning of the arbitrary day, and the ashtrays were spilling onto the desk.

“Look,” he said, “if they were going to let him go, why did they carefully make an exhibition piece out of him.”

Willis rubbed a hand over his stubble. “Assuming he is Martini, there’s a strong possibility they had no intention of ever doing so. I’d say, in that case, they figure he’d be grateful enough to them so he’d volunteer to help. Particularly since he’s an engineer. It seems reasonable he’d be impressed with their work on a purely professional level, as well. I’m impressed––but then, I’m no engineer.”

“Barrister’s impressed,” Rogers told him. “So am I.” He lit a new cigarette, grimacing at the taste. “We’ve been over this before. What does it prove?”

“Well, as I said, they may not have had any intention of ever letting him see us. But if he did hold out, despite their calculations and interrogations, that puts a new face on it. Our side put an awful lot of pressure on them. They may have decided, later, that he wasn’t the gold mine they’d expected. Let’s say they’ve got something else planned––next month, say, or next week. They figure if they give us Martini, maybe they can get away with their next stunt.”

Rogers crushed the cigarette out. “What’s he got to say on the subject?”

Willis shrugged. “He says they made him some offers. He figured they were just bait, so he turned them down. He says they interrogated him and he didn’t crack.”

“Think it’s possible?”

“Anything’s possible. He hasn’t gone insane yet. That’s something in itself. He was always a pretty well-balanced individual.”

Rogers snorted. “Look––they’ve cracked everybody they ever wanted to crack. Why not him?”

Willis shrugged again. “I’m not saying they didn’t. But there’s a possibility he’s Grade A. Maybe they didn’t have enough time. Maybe he did have an advantage. Not having mobile features and a convulsive respiratory cycle to show when they had him close to the ragged edge. His heartbeat’s no indicator, either, with a good part of its load taken over by his powerplant. His whole metabolic cycle’s non-kosher.”

Willis threw up his hands. “How much do you know about Russians?” he asked.

Rogers looked at him curiously. “About as much as the next guy. Nyet, nichevo, harasho, panimayet Parusski? Why?”

Willis shrugged. “Well, it’s a trap to generalize about these things. But I keep thinking; whether it started out that way or not, every one of them that knows about Martini is laughing his hair off at us. They go in for practical jokes. Deadpan. I’ve got a vision of the boys, clustered around the vodka, laughing and laughing and laughing.

“It all adds spice to the cake.”

Rogers grunted sourly and wiped a hand across his sweated upper lip. “Look,” he said doggedly, ticking off each point on his fingers, “there are three main possibilities:

“One, he’s Martini and he didn’t crack.

“Two, he’s Martini and he did crack.

“Three, he isn’t Martini. I’ll give him credit. If he isn’t, he knows he’s getting closer to permanent disappearance every minute. He’s not showing it.

“Now––if he belongs to the first category, he’ll be all right. He’ll be shipped to some quiet place and given a lot of gadgets to tinker with while he’s waiting for that pile to kill him. If he’s in the second, substantially the same thing will happen to him.”

“Until the pressure of knowing he’s a dead man piles up on top of what he’s already like, and he goes insane,” Willis said.

“Or until,” Rogers acknowledged. “But––I don’t have to worry so much about that second category. All I have to do is reach a decision as to whether he is or isn’t Martini. Anything I may find out in the process is pure gravy. It doesn’t really matter, immediately, if he cracked. K–88 has definitely been scrubbed, and that’s the only big thing he could have helped them on.

“Once he’s put away somewhere, we’ve got the rest of his life to do a careful psychological analysis. All I need right now is one clue––just one sign that he’s Martini. Let’s face it––despite everything we’ve tried, we can’t prove he isn’t. All it takes to tip the scale one way or the other is a strong hint.

“But until I find out, we’re stalled. If he isn’t Martini, he might be anything. He might have abilities we don’t know about. He might be primed to fission that pile in the middle of Leyport––with subsequent regrets and explanations of mechanical failure from our neighbor People’s Democracies.”

Willis nodded in sympathy. “What’s this about his fingerprints, though?”

Rogers almost cursed. “His right shoulder’s a mass of scar tissue. If they can substitute mechanical parts for eyes and ears and lungs––if they can motorize an arm, and hook the whole thing to his appropriate brain centers…”

Willis turned pale. “You mean––that isn’t necessarily Martini, but it’s definitely Martini’s right arm?”

“Exactly.”

Rogers could feel the trembling in his calves. They’d had Martini for three weeks, now.

You take specialists. You get the best mechanical engineer on the Moon, and give him a staff. You take the FBI’s top agent. You borrow the best psychometrician and steal the President’s personal psychologist. You give them assistants. You fling them at that iron mask––and watch them bounce helplessly away.

If your name is Sam Rogers, you’re ready to crack.

How do you pry open the mask and get at somebody who, maybe, was once Luke Martini, a kid fist-fighting his way to and from grammar school in Bridgeton, New Jersey, USA.

How did you go about it?

Or had he been a tow-headed, blocky kid carrying the banner of the Komsomol? And fist-fighting on his way home from the parade, of course. Particularly if there were some kids with Asiatic blood living where he was.

Good Lord!

Rogers burst open the door of Martini’s room. The man was lying on his bunk, smoking. His head jerked up as the door rebounded against the wall.

“All right,” Rogers grated savagely, “on your feet, Wop!”

Martini half-sprang at him, the metallic curse ringing in his mouth. Then he stopped, his murderous hand slowly dropping to his side, along with the fleshly one. He eye-shutter snapped wide open.

Rogers sighed slowly. Then he grinned. “Okay, Martini, you pass,” he said. He backed out of the room, closing the door gently. Even where they were sobs of relief, it was unsettling to hear a man cry if he had no tears.

Algis Budrys

Tim Powers on Who?

Read Biography

Algis Budrys—“Who?” The Original Short Story

Like more than a few of the 1950s’ classic science fiction novels, Algis Budrys’s Who? began as a short story. He wrote it––he later claimed––having been inspired by a Kelly Freas painting he had seen in the offices of Fantastic Universe, and published it in that magazine in April 1955. Here is the original “Who?”A Conversation with Algis Budrys

Algis Budrys discusses his novel Who?, along with many other subjects, in this interview with Darrell Schweitzer published in Amazing Stories in November 1981.Audio: Algis Budrys—“Protective Mimicry” on X Minus One (1956)

Other Novels by Algis Budrys