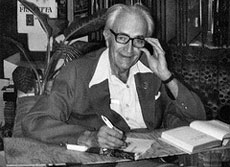

Fritz Leiber remembers how he came to write The Big Time in this introduction to the novel, added to a new edition in 1982.

The Big Time: An Introduction (1982)

The remaining interior wall of the demolished building had on it the pattern of what had been destroyed: three floors and a stairway; grimy but with lighter rectangles where pictures had been hung on it or furniture set against it; a commanding and haunted flat expanse.

My friend Art Kuhl, author of Royal Road and the still more impressive novel Obit. (as far as I know never published) said, “What a challenge to Gully Jimson!” He was surprised to find I’d never read Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth and so knew nothing of the rapscallion old painter who could never see a big empty wall without feeling the irresistible urge to paint a mural on it, whether it was coming down tomorrow or not.

I respected Art. I read the book at once and also the two other novels in the trilogy, Herself Surprised and To Be a Pilgrim, which cover the same events from three different viewpoints, and was struck by their style of what can be called intensified and embellished first person: not only is each story told by one person, but he or she has a unique and highly colorful way of speaking, with all sorts of vivid little eccentricities of language––they even think to themselves differently.

So (although I didn’t know it at once) Greta Forzane was born, with her punning religious ejaculations and her frank, cool, deliberately cute way of speaking––always the little girl putting on an ingratiating comedy act.

I hadn’t written anything for four years, my longest dry spell. I knew from experience that at such times a first-person story is the easiest way to break silence––it solves the problem of what you can tell and what you can’t, whereas in a third-person story you can bring in anything, an embarrassment of riches, and I determined that my next story would be in the intensified first person of Joyce Cary.

I’ve always been fascinated by time-travel tales in which soldiers are recruited from different ages to serve side by side in one war––there’s something irresistible about putting a Doughboy, a Hussar, a Landsknecht and a Roman Legionary in one tent––and it’s also exciting to think of a war fought in and across time, where battles can actually change the past (one of the truly impossibles, but who knows? Olaf Stapledon wrote about swinging it)––it’s an old minor theme in science fiction; I remember stories by Ed Hamilton and, I think, Jack Williamson. I determined to write such a story and to put the emphasis on the soldiers rather than on the two (or More?) warring powers. Those would be big and shadowy, so you couldn’t be altogether sure which side you were fighting on and at the very best you’d have only the feeling that you were defending something bad against something worse––the familiar predicament of man.

To keep the focus on a few individuals, I put the story in one setting, a small rest and recreation center staffed by entertainers who were also therapists––some of them sex therapists, a concept that had rather more novelty back in 1956 and early 1957, which was when I wrote this rather short novel (in exactly a hundred days from first note to final typing finished, it counted out). The words got to flowing rather fast and fluently for me––when I start to type phonetically (“I” for “eye,” “to” and “too” and “two” interchangeable) I know I’m hot––though I rarely did more than a thousand a day. I tried the experiment of playing music to start myself off each day and this time it worked. The pieces were Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Pathetique piano sonata and the Schubert Unfinished. The book is also keyed to the two songs “Gentlemen Rankers” and “Lili Marlene” and I sometimes played those two. (The only quotation haunting me that didn’t get into the book was from a Noel Coward song, “We’re all of us just rotten to the core, Maud.”)

My plot was ready made. My disillusioned soldiers would try to resign from the war and set up a little utopia, like Spartacus and his gladiators, and then find out that they couldn’t, “for there’s no discharge from the war”––another familiar human predicament.

To dramatize the effects of time travel, science fiction usually assumes that if you could go back and change one crucial event, the entire future would be drastically altered––as in Ward Moore’s great novel Bring the Jubilee where the Southrons seize the Round Tops at the start and win the Battle of Gettysburg and the Civil War (and then lose it again, heartbreakingly, when the hero goes back and unintentionally changes that same circumstance). But that wouldn’t have suited my purposes, so I assumed a Law of the Conservation of Reality, meaning that the past would resist change (temporal reluctance) and tend to work back quickly into its old course, and you’d have to go back and make many little changes, sometimes over and over again, before you could get a really big change going––perhaps the equivalent of an atomic chain reaction. It still seems to me a plausible assumption, reflecting the tenacity of events and the difficulty of achieving anything of real significance in this cosmos––a measure of the strength of the powers that be.

The energy I generated writing this novel of the Change War of the Spiders and Snakes (as I called the two sides, to keep them mysterious and unpleasant, as major powers always are, inscrutable and nasty) overflowed at once into two related short stories, “Try and Change the Past” and “Damnation Morning,” and later into two others, “The Oldest Soldier” and “Knight to Move,” but it wasn’t until 1963 that I did a short novelette with most of the same characters, “No Great Magic,” where my entertainers have become a travelling theatrical repertory company putting on performances, mostly one-night-stands, across space and time, and under that cover working their little changes in the fabric of history, nibbling like mice at the foundations of the universe––now they were becoming soldiers themselves as well as entertainers. An anachronistic performance of Macbeth for Elizabeth the First and for Shakespeare himself tied the story together and gave it dramatic unity, while I had to give Greta Fontane amnesia, so she could learn about the Change War all over again.

The story allowed me to draw on my own Shakespearean experiences and (once planned––it began as a modern tale of an agoraphobic young woman who literally lived in a dressing room, no Change War or science fantasy at all as first conceived) was remarkably quick in being written––ten days as I recall.

I’m still trying to write the sequel to that one––and still hope to do so one day; at least it’s one of my penultimate projects.

Fritz Leiber

Neil Gaiman on The Big Time

Read Biography

Fritz Leiber—The Big Time: An Introduction

Fritz Leiber remembers how he came to write The Big Time in this introduction to the novel, added to a new edition in 1982.Foreword to The Mind Spider and Other Stories

Fritz Leiber Bonus Material

Here are three 1950s radio adaptations of Leiber's stories from the NBC radio program X Minus One plus five Change War stories exploring the war between Spiders and Snakes in The Big Time.Other Novels by Fritz Leiber