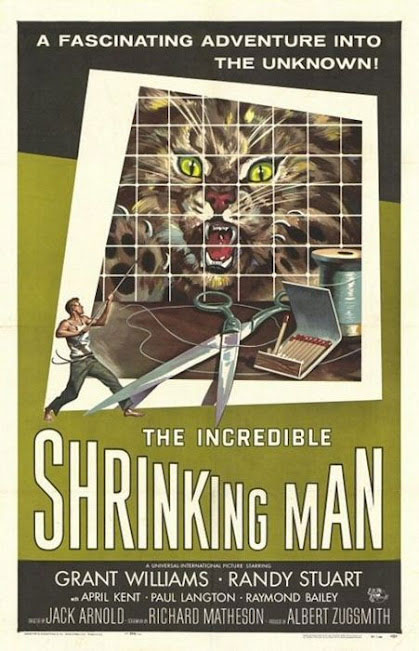

Peter Straub on The Shrinking Man

Richard Matheson, at this writing still publishing in his ninetieth year, is the most varied and intellectually agile of the community of fantasy/sci-fi/horror writers that gathered in Los Angeles in the mid-fifties to create, along with a great many Twilight Zone episodes, a body of short stories and novels that brought sleeker, more refined and efficient aesthetic to the Weird Tales model they had absorbed from H. P. Lovecraft. Ray Bradbury, who by the mid-fifties had lived in Los Angeles for two decades, was in some sense the alpha dog of those writers—Charles Beaumont, Bill Nolan, Harlan Ellison, George Clayton Johnson—who provided scripts for Rod Serling’s adventurous new television series. But if these men set Bradbury apart by almost literally revering him, Richard Matheson was their point man, an equal who nonetheless had more on the ball than the rest of the pack. Robert Bloch, a close friend to all parties, once explained his absence from Twilight Zone by saying that it was safe “in the hands of . . . the Matheson Mafia—Beaumont, Nolan, Johnson, and other friends.” That is, their work could by summed up by the mention of his name.

These men, along with Bloch, had perfected a clean, craftsmanly sub-genre that could be called California Gothic. Their stories were as carefully engineered as haikus and as intolerant of wasted motion. Every line of dialogue, every observed detail, hastened the story forward toward a conclusion that upended all we had imagined them to mean. Trick endings, twist endings, shock endings, if you make them the core of your aesthetic you create a literature of steely, ironic misdirection narrated to bamboozled readers by unreliable characters. Digression, self-indulgence, and pretension are disallowed, strenuously.

No one was better than Matheson at demonstrating the many uses of this variety of minimalism, but it did contain one unshakeable limitation, that it was designed for the production of short fiction. However, in the right hands the method did allow for a cautious expansion. The rest of “the Matheson Mafia” succeeded in writing no more than two or three novels each. (Some of them had zero interest in novels.) Matheson, however, who started novelizing early on and just kept going, has now written twenty-eight. The Shrinking Man was the fourth of these, and like its immediate predecessor, I Am Legend, it brilliantly aerates the minimalist aesthetic of its time and place by linking it to an episodic structure in which each of the episodes serves further to tighten the narrative noose.

Episodic narratives never work like this, that’s what makes them episodic. A narrative consisting entirely of episodes and connective tissue generally careens all over the map like Odysseus and Don Quixote, gathering and losing steam as it goes. As in Rogue Male, Geoffrey Household’s masterpiece, The Shrinking Man begins with its First Cause, then traces the unfolding consequences of that event in a close-up, one-to-one, unswerving manner that sweeps us ever closer to what may not after all prove impossible in a first-person novel, the protagonist’s extinction. It might not be death, exactly, but it should be the next closest thing, total disappearance. In 1953, Matheson had not yet moved beyond the desire to finish a tale with a surprise ending, but what he found here is a real surprise, filled not with deadpan professional cynicism but serenity and optimism—a fresh, wide-eyed step into a world both beautiful and new.

Richard Matheson

Peter Straub on The Shrinking Man

Read Biography

Richard Matheson—The Shrinking Man: An Introduction

Richard Matheson described the writing of his novel The Shrinking Man in this new introduction, written for a limited edition published in 2001.

The Novelist Goes to Hollywood: Three Letters on The Shrinking Man (1955–56)

Audio: Richard Matheson reads from The Shrinking Man (1956)

Other Novels by Richard Matheson