Michael Dirda on The Space Merchants

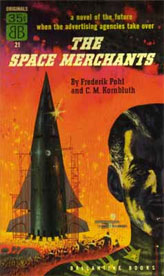

Advertising Age is the name of Madison Avenue's trade magazine, but it also neatly sums up the world of The Space Merchants. Sometime in the distant future—the presidency has become an inherited position—the United States is largely controlled by two rival advertising agencies, Fowler Schocken Associates and B. J. Taunton. By this time, cities have also grown so overcrowded that people rent bedspace in stairwells, water is a precious commodity, organic foods have been replaced by artificial substitutes, and corporate rivalries can lead to legally sanctioned feuds and assassinations.

Most of all, people in power worry about the clandestine World Conservationist Association, regarded by all right-thinking Americans as a terrorist group that opposes everything that a commercial society stands for and believes in, from subliminal marketing to the fullest possible exploitation of the earth's natural resources. While passing as upstanding members of the consumer society, the Consies are actually determined to overturn the established order and build what they deludedly regard as a better, more equitable world.

Just as George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four intensifies the ideologies and politics of 1948, so The Space Merchants extrapolates from the business life and patriotic fears of 1950s America. That postwar decade was the hard-charging age of the man in the gray-flannel suit, a time of hucksters and status-seekers and keeping up with the Joneses. It was also the era of the Red Scare when anyone—even your kindly neighbor next door, perhaps especially your kindly neighbor next door—might be a Communist agent plotting the complete destruction of the American Way of Life.

Does this mean that The Space Merchants is a dark dystopian novel? A wry commentary on the Cold War? Or a Phildickian vision of a run-down future when even bigshots rely on pedal-powered Cadillacs? Yes, to all—in part. Today, though, the novel more often seems the science fictional equivalent of a Preston Sturges comedy, lightly satirical, with many twists, and extremely fast-paced, though still addressing serious moral and societal questions. As in a film like Sullivan's Travels, The Space Merchants quickly pulls an attractive but self-satisfied hero into a series of crises that ultimately results in his moral redemption and a new understanding of the world.

From its first sentence, the book's tone is brassy, cocky, sure of itself:

As I dressed that morning I ran over in my mind the long list of statistics, evasions, and exaggerations that they would expect in my report.

To the reader that's funny, but it's just business as usual to the speaker (and the book's protagonist), Mitchell Courtenay. Mitch, a star-class copysmith, believes wholeheartedly in Fowler Schocken Associates, in the gods of Advertising and Sales, in his right to all the perks that his elevated rank permits him. He shrugs off the Consies as nothing but "wild-eyed zealots who pretended modern civilization was in some way 'plundering' our planet. Preposterous stuff. Science is always a step ahead of the failure of natural resources. After all, when real meat got scarce, we had soyaburgers ready. When oil ran low, technology developed the pedicab."

Given such smugness, comeuppance can't be long in coming. When Mitch takes over an account to sell Venus—deadly, inhospitable Venus—as a paradise for colonists, he suddenly finds his comfortable existence crumbling around him.

As the story picks up speed, much of the reader's pleasure derives from regularly administered jolts of surprise, whether in dramatic plot developments or in Mitch's throwaway comments about ordinary life. One doesn't buy, one rents, a newspaper. An expensive engagement ring is made of oak. The legal system argues that it is far better for innocent people to be convicted than to allow one guilty man to go free. Mitch even confesses that he doesn't "go much for religion—partly, I suppose, because it's a Taunton account."

Above all, Pohl and Kornbluth keep driving home how crowded the United States has grown, how few natural resources remain. An elite country club is merely a big room where people play video golf and tennis. In Manhattan there are "hundreds of acres of rooftops where men and women could walk around in the open air, wearing simple soot-extractor nostril plugs instead of a bulky oxygen helmet." When getting cleaned up after work, Mitch observes that "there was only one other man in the shower, but, with only two of us, we hardly touched."

Science fiction has always specialized in world-building, in bringing vivid life to an imagined future or alien civilization—and in this Pohl and Kornbluth certainly succeed. More problematic, though, are their novel's sometimes cringe-making references to sex and the relationships between men and women. Mitch supposedly adores his "provisional" wife Kathy, but he wants her to stop being a surgeon and become a housewife. At one point he even slugs her, and for a while acts like Mike Hammer, the sadistically macho private eye of contemporary novelist Mickey Spillane. At Fowler Schocken, one hard-working female copysmith is snickeringly gossiped about as easy. And naturally, any good secretary is willing to sacrifice her life for the boss she secretly adores, just as any real man is driven apoplectic when subjected to a homosexual pass. A few elements of the book almost approach the kinky: the most sexually desirable human being on the planet is, as a result of an intense media campaign, a 35-inch-tall midget named Jack O'Shea.

As a novel, The Space Merchants feels loose and almost improvisational in its construction, even as its humor can sometimes seem broad and dated. But read as a period piece, it possesses that distinct sprightliness and desire to please we love in so much 1950s art and culture. Within science fiction itself, the book remains one of the genre's great patterning works of social satire, looking forward to such later classics as Kurt Vonnegut's The Sirens of Titan and the black-humored fiction of John Sladek and Thomas M. Disch.

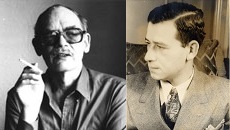

Frederik Pohl & C. M. Kornbluth

Michael Dirda on The Space Merchants

Read Biography

Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth—The Space Merchants: An Alternate Ending

Sometime around February 1952, having sent a finished draft of the novel eventually published as The Space Merchants off to Horace Gold at Galaxy magazine, Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth got the news that there was “a kind of hitch” in their plans for the book: it wasn’t long enough. Gold needed several thousand additional words to fill up the space he had allotted for the novel, which he was publishing in Galaxy as Gravy Planet.Frederik Pohl—"Cyril": Remembering C. M. Kornbluth

Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth met as teenage members of the Futurian Society, a New York fan group, and their intensely productive friendship was cut short only by Kornbluth's premature death, of a heart attack, at 34. Here, in an April 20, 2009, post from his lauded blog ("The Way the Future Blogs"), Pohl remembers his coauthor.C. M. Kornbluth—The Failure of the Science Fiction Novel as Social Criticism

In 1957, C. M. Kornbluth participated in a lecture series at the University of Chicago featuring leading SF writers.Pohl & Kornbluth

Bonus Material

Radio dramatizations of The Space Merchants and four of Frederik Pohl's science fiction stories, plus video of C. M. Kornbluth's “The Little Black Bag” on Tales of Tomorrow (1952).

Other Novels by Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth