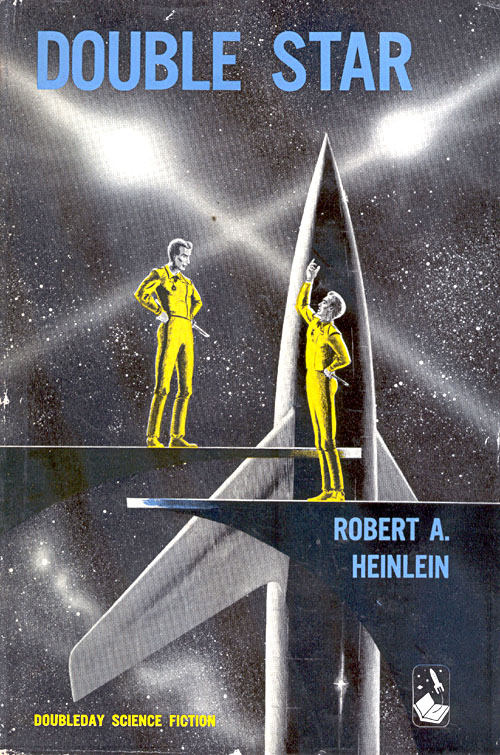

Connie Willis on Double Star

Of all Heinlein’s books, his short novel Double Star is one of my three favorites. (The other two are Have Space Suit, Will Travel, and The Door into Summer.) It has all the things I love most about Heinlein’s writing: his can’t-put-it-down storytelling, his humorous, breezy style, his easy-to-identify-with characters, and his inventiveness in creating other worlds. And other times.

One of those times is the richly imagined future of Double Star. It’s full of space yachts and hush corners, Martian induction ceremonies and injection guns and interplanetary empires, yet everything seems completely believable. Heinlein’s forte was always his ability to create a convincing future without letting it take over the story and to make it seem like a real—and familiar—place.

He doesn’t walk us through his futures, pointing out the amazing inventions and advances. His characters live there. To them it’s as familiar and ordinary as the present is to us. In Double Star, we find out about bounce tubes because his hero Lorenzo doesn’t have enough money to take one, and about the Moon shuttle because he’s spectacularly sick on it. Neither is explained, and neither are dropsickness or Silicoflesh or autosecretaries. Yet, because of Heinlein’s facility in inventing names and providing context, they don’t need to be. And we’re too caught up in the story to worry about explanations. Within half a page, Lorenzo has met a suspect stranger. Within one and a half, he’s been offered a mysterious job, and within twelve, he’s in completely over his head and frantically trying to find a way out. And that’s just the beginning.

The basic plot of Double Star, that of someone doubling for his look-alike, has been around forever, and it’s been used by everyone from Dickens (A Tale of Two Cities) to Dumas (The Count of Monte Cristo) to the movies Dave and Vantage Point to real life.

The last in that list may well have served as the inspiration for Double Star. When I was researching British Intelligence’s World War II deception campaigns for my novels Blackout and All Clear, I came across the intriguing story of an actor who doubled for General Montgomery just before the D-Day invasion. He was sent to Gibraltar (Monty was busy in England planning the invasion) to convince the Nazis the invasion wouldn’t happen till later in the summer and to make them think it might be staged from the Mediterranean.

The minute I read about the deception, I thought of Double Star and wondered if that was where Heinlein got the idea for it. The timing’s right: the actor, Clifton James, wrote a book about his experience called I Was Monty’s Double, which came out in 1954, and Double Star was first published in installments in Astounding in 1956. I can’t prove the connection, but there are similarities in the hero’s being an actor and in his having to impersonate a political figure in dangerous and potentially deadly circumstances.

Or Heinlein might have been inspired by Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper or Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda. Or simply by the obvious dramatic possibilities of one person having to pretend to be another.

But wherever he got the idea, he made it his own, bringing his own unique slant and style to the book, and his considerable storytelling ability. Double Star’s full of steadily rising stakes, sudden reversals, and all sorts of plot developments that keep the reader off-balance. I still remember the shock of surprise I got the first time I read the ending, and rereading it all these years later, I still find myself surprised by the twists and turns the story takes.

But though plot is what keeps us reading, it isn’t what makes us care about what happens. It’s a story’s characters that do that, and Double Star has some great ones, from the daring, take-charge Dak Broadbent to the missing Right Honorable John Joseph Bonforte who makes the impersonation necessary, to the Scotch-drinking and far too perceptive King Willem. My favorite character is Penny, who seems at first to be a very 1950s secretary-in-love-with-her-boss, but who (just like everyone else in the book) isn’t quite what she seems.

The best character is of course the hero, that out-of-work, down-on-his-luck actor who’s nevertheless very impressed with himself and his abilities. Lorenzo Smythe is one of the best heroes Heinlein ever created. He’s cocky, conceited, not particularly brave, out of his depth, and, eventually, a hero. And definitely more than he at first appears. The perfect central character for a story which is all about identity, about the people we start out as and that circumstances—and fate—make us into.

Double Star also a love story. And a tale of the often-dirty dealings of politics. And, along the way, Heinlein manages to work in discussions of civil rights and what constitutes a human being, of terrorism and theories of government and what sort of people we need to be in a future in which we’re not the only sentient species.

But that makes it sound like Double Star is ponderous and preachy. It’s not. Heinlein’s other great gift was his ability to tell thought-provoking stories and examine serious issues in a light, effortless manner, and that’s on full display here. Double Star is quick-paced, often funny, and always entertaining.

Heinlein’s novels of the 1940s and 50s shaped every single science fiction writer of my generation and everyone currently writing science fiction. Or making science fiction movies. Star Wars, with its light-hearted banter and banged-up spaceships, was set squarely in Heinlein territory. So was Star Trek, and so are today’s Firefly and Primeval. Heinlein was the most influential writer for everyone writing in science fiction today—and Double Star is an excellent example of all the reasons why.

Robert Heinlein

Connie Willis on Double Star

Read Biography

Science Fiction: Its Nature, Faults and Virtues

Audio: Robert A. Heinlein Stories on 1950s Radio: Dimension X (1950–51)

Five of Heinlein's science fiction stories were adapted for the NBC radio series Dimension X in 1950–51. "Destination Moon"—adapted from the 1950 Destination Moon screenplay, on which Heinlein collaborated—aired on June 24, 1950. "The Roads Must Roll"—published in Astounding Science Fiction, June 1940—aired on September 1, 1950. "Universe" (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1941) aired on November 25, 1950. "The Green Hills of Earth" (Saturday Evening Post, February 8, 1947) aired on December 24, 1950. "Requiem" (Astounding Science Fiction, January 1940) aired on September 22, 1951.Other Novels by Robert Heinlein

Credit: G Mark Photography

Credit: G Mark Photography