Kit Reed on More Than Human

I didn't learn to write in the classroom, or from a how-to book. Tough city editors taught me discipline and precision, and they weren't kidding. Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Evelyn Waugh did the rest, along with Iris Murdoch, Bradbury, Graham Greene, Salinger, who else? L. Frank Baum and Ruth Plumly Thompson; Muriel Spark, but only a little bit. I was too young to know what I was doing, but I wanted more than anything to be good at it.

This year I reread Theodore Sturgeon's More than Human. How could I leave him off the list? I read a lot of SF as a kid, trailblazers like Wells and Verne, Orwell and Huxley; I read Out of the Silent Planet by C. S. Lewis, who fused theology and fantasy. I read Heinlein, Asimov, Bradbury, Pohl, and Kornbluth, too many others to list, all at a dead run.

I read so much, so fast, that time blurs memory.

Of all the novels I read, Theodore Sturgeon's brilliant, flawed pastiche is the one I still talk about. It's still risky, exciting and fresh. My early stories were weird but pretty linear. He showed me how to open them up.

In the days when straightforward stories about rocketry and robotics, alien cultures and dystopic futures were the norm in science fiction, Sturgeon cared about how his characters felt, and what they thought. Risky as it was, he explored new ways to move his characters—and his readers—through time and space, from the mind of one point-of-view character to the next.

In More Than Human, Sturgeon plays with ideas, zooming back and forth in an expanding conceptual space. He's a born stylist ready and willing to take narrative risks. He uses timing, cadence, selection, everything at hand to shape his story so organically that there's no separating the story from the telling.

In Part One Sturgeon introduces Lone, the tabula rasa whose consciousness expands as he connects with the others in "The Fabulous Idiot." We meet the Kews and their nightmare father; the Prodds, who take the idiot in; Janie, the rebellious telepath, and her pals the kinesthetic twins; grubby, hostile Gerry, whom I never liked much; Hip, golden boy and genius, interweaving their stories with tremendous skill.

Sturgeon writes: "He [the idiot] carried another thing. It was passive, it was receptive, it was awake and alive. It took what it took and gave back nothing. All around it, to its special senses, was a murmur, a sending . . . . " He is laying the first stepping-stone.

With his confidence in his characters, his ability to read their minds and take us anywhere, anywhen, Sturgeon can do anything he wants.

Abrasive Gerry narrates "Baby Is Three," the least successful section of the book. Although the switch to tight first-person after the dazzling opening showed me new technical possibilities, the book slows down. I didn't like Gerry's tone, but maybe that's my problem, not the author's.

Gerry's shrink gets the best lines in Part Two, laying another stepping-stone in Sturgeon's path to the ending:

". . . There's a chain of solid, unassailable logic in the things we do. Dig deep enough and you find cause and effect as clearly in this field as you do in any other," he says—an intensely Thomistic thought. And given the conclusions Sturgeon reaches in Part Three, "Morality," it seems absolutely right.

What I loved best about the book when I first read it, what I love now, is the moment of convergence, the narrative snap at the end, when all the characters meet and become the group mind. Everybody figures: Baby, Janie and the twins, Lone and the tool he devised to get Prodd's truck out of the mud; Hip, the burned-out genius. Everything, from the group's hidden powers to principles of psychology and physics, falls into place and the gestalt comes to life.

"There was a happy and fearless communion, fearlessly shared with Gerry," who reflects, "And now . . . is it the ethic? Is that what completed me?"

To which the group mind responds: "Ethic is too simple a term. But yes, yes . . . multiplicity is our first characteristic; unity our second. As your parts know they are parts of you, so must you know that we are parts of humanity."

What did Sturgeon teach me? That everybody can grow and change; that a good story can use anything it wants to tell itself.

That if I care as much about craft, what I have to say and how I say it as Sturgeon did, if I'm smart enough and work hard enough, I can write anything I want, any way I want.

Theodore Sturgeon

Kit Reed on More Than Human

Read Biography

Theodore Sturgeon—More Than Human: An Introduction

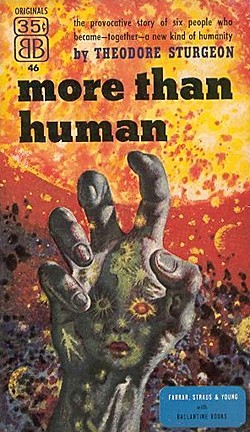

Well received when it was first published in 1953, More Than Human became even more popular as years went by, and in 1978 it was adapted as a graphic novel. Sturgeon took the occasion to describe the circumstances in which he wrote the novel.

Theodore Sturgeon

Bonus Material

Audio of Sturgeon reading from More Than Human, on 1950s radio program X Minus One (1956–57), and video of Sturgeon on Tales of Tomorrow (1951).

Other Novels by Theodore Sturgeon

Credit: Beth Gwynn

Credit: Beth Gwynn