Damnation Morning

Fantastic, August 1959

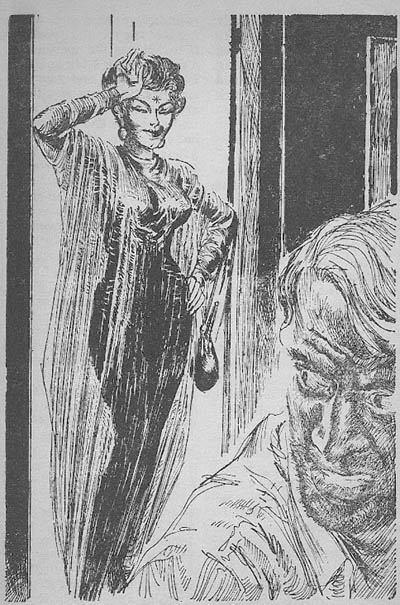

illustration by Leo Summers, Fantastic, August 1959

illustration by Leo Summers, Fantastic, August 1959

Time traveling, which is not quite the good clean boyish fun it’s cracked up to be, started for me when this woman with the sigil on her forehead looked in on me from the open doorway of the hotel bedroom where I’d hidden myself and the bottles and asked me, “Look, Buster, do you want to live?”

It was the sort of question would have suited a religious crackpot of the strong-arm, save-your-soul variety, but she didn’t look like one. And I might very well have answered it—in fact, I almost did—with a hangover, one-percent humorous, “Good God, no!” Or—a poor second—I could have studied the dark, dust-burnished arabesques of the faded blue carpet for a perversely long time and then countered with a grudging, “Oh, if you insist.”

But I didn’t, perhaps because there didn’t seem to be anything like one percent of humor in the situation. Point One: I have been blacked out the past half hour or so—this woman might just have opened the door or she might have been watching me for ten minutes. Point Two: I was in the fringes of DTs, trying to come off a big drunk. Point Three: I knew for certain that I had just killed someone or left him or her to die, though I hadn’t the faintest idea of whom or why.

Let me try to picture my state of mind a little more vividly. My consciousness, the sentient self-aware part of me, was a single quivering point in the center of an endless plane vibrating harshly with misery and menace. I was like a man in a rowboat in the middle of the Pacific—or better, I was like a man in a shellhole in the North African desert (I served under Montgomery and any region adjoining the DTs is certainly a No Man’s Land). Around me, in every direction—this is my consciousness I’m describing, remember—miles of flat burning sand, nothing more. Way beyond the horizon were two divorced wives, some estranged children, assorted jobs, and other unexceptional wreckage. Much closer, but still beyond the horizon, were State Hospital (twice) and Psycho (four times). Shallowly buried very near at hand, or perhaps blackening in the open just behind me in the shellhole, was the person I had killed.

But remember that I knew I had killed a real person. That wasn’t anything allegorical.

Now for a little more detail on this “Look, Buster” woman. To begin with, she didn’t resemble any part of the DTs or its outlying kingdoms, though an amateur might have thought differently—especially if he had given too much weight to the sigil on her forehead. But it was no amateur.

She seemed about my age––forty-five––but I couldn’t be sure. Her body looked younger than that, her face older; both were trim and had seen a lot of use, I got the impression. She was wearing black sandals and a black unbelted tunic with just a hint of the sack dress to it, yet she seemed dressed for the street. It occurred to me even then (off-track ideas can come to you very swiftly and sharply in the DT outskirts) that is was a costume that, except perhaps for the color, would have fitted into any number of historical eras: old Egypt, Greece, maybe the Directoire, World War I, Burma, Yucatan, to name some. (Should I ask her if she spoke Mayathan? I didn’t, but I don’t think the question would have fazed her; she seemed altogether sophisticated, a real cosmopolite––she pronounced “Buster” as if it were part of a curious, somewhat ridiculous jargon she was using for shock purposes.)

From her left arm hung a black handbag that closed with a drawstring and from which protruded the tip of a silvery object about which I found myself apprehensively curious.

Her right arm was raised and bent, the elbow touching the door frame, the hand brushing back the very dark bangs from her forehead to show me the sigil, as if that had a bearing on her question.

The sigil was an eight-limbed asterisk made of fine dark lines and about as big as a silver dollar. An X superimposed on a plus sign. It looked permanent.

Except for the bangs she wore her hair pinned up. Her ears were flat, thin-edged, and nicely shaped, with the long lobes that in Chinese art mark the philosopher. Small square silver flats with rounded corners ornamented them.

Her face might have been painted by Toulouse-Lautrec or Degas. The skin was webbed with very fine lines; the eyes were darkly shadowed and there was a touch of green on the lids (Egyptian?—I asked myself); her mouth was wide, tolerant, but realistic. Yes, beyond all else, she seemed realistic.

And as I’ve indicated, I was ready for realism, so when she asked, “Do you want to live?” I somehow managed not to let slip any of the flippant answers that came flocking into my mouth. I realized that this was the one time in a million when a big question is really meant and your answer really counts and there are no second chances, I realized that the line of my life had come to one of those points where there’s a kink in it and the wrong (or maybe the right) tug can break it and that she knew all about this—that as far as I was concerned at the present moment, she knew all about everything.

So I thought for a bit, not long, and I answered, “Yes.”

She nodded—not as if she approved my decision, or disapproved it for that matter, but merely as if she accepted it as a basis for negotiations—and she let her bangs fall back across her forehead. Then she gave me a quick dry smile and she said, “In that case you and I have got to get out of here and do some talking.”

For me that smile was the first break in the shell—the shell around my rancid consciousness or perhaps the dark, star-pricked shell around the space-time continuum.

“Come on,” she said. “No, just as you are. Don’t stop for anything and—” (She caught the direction of my immediate natural movement) “—don’t look behind you if you meant that about wanting to live.”

Ordinarily being told not to look behind you is a remarkably silly piece of advice, it makes you think of those “pursuing fiend” horror stories that scare children, and you look around automatically—if only to prove you’re no child. Also in this present case there was my very real and dreadful curiosity: I wanted terribly (yes, terribly) to know whom it was I had just killed—a forgotten third wife? a stray woman? a jealous husband or boyfriend? (though I seemed too cracked up for love affairs) the hotel clerk? a fellow derelict?

But somehow, as with her “want to live” question, I had the sense to realize that this was one of those times when the usually silly statement is dead serious, that she meant her warning quite literally.

If I looked behind me, I would die.

I looked straight ahead as I stepped past the scattered brown empty bottles and the thin fume mounting from the tiny crater in the carpet where I’d dropped a live cigarette.

As I followed her through the door I caught, from the window behind me, the distant note of a police siren.

Before we reached the elevator the siren was nearer and it sounded as if the fire department had been called out too.

I saw a silvery flicker ahead. There was a big mirror facing the elevators.

“What I told you about not looking behind you goes for mirrors too,” my conductress informed me. “Until I tell you differently.”

The instant she said that, I knew that I had forgotten what I looked like; I simply could not visualize that dreadful witness (generally inhabiting a smeary bathroom mirror) of so many foggy mornings: my own face. One glance in the mirror . . .

But I told myself: realism. I saw a blur of brown shoes and black sandals in the big mirror, nothing more.

The cage of the right-hand elevator, dark and empty, was stopped at this floor. A cross-wise wooden bar held the door open. My conductress removed the bar and we stepped inside. The door closed and she touched the controls. I wondered, “Which way will it go? Sideways?”

It began to sink normally. I started to touch my face, but didn’t. I started to try to remember my name, but stopped. It would be bad tactics, I thought, to let myself become aware of any more gaps in my knowledge. I knew I was alive. I would stick with that for a while.

The cage sank two and a half floors and stopped, its doorway blocked by the drab purple wall of the shaft. My conductress switched on the tiny dome light and turned to me.

“Well?” she said.

I put my last thought into words.

“I’m alive,” I said, “and I’m in your hands.”

She laughed lightly. “You find it a compromising situation? But you’re quite correct. You accepted life from me, or through me, rather. Does that suggest anything to you?”

My memory may have been lousy, but another, long unused section of my mind was clicking. “When you get anything,” I said, “you have to pay for it and sometimes money isn’t enough, though I’ve only once or twice been in situations where money didn’t help.”

“Three times now,” she said. “Here is how it stacks up: You’ve bought your way, with something other than money, into an organization of which I am an agent. Or perhaps you’d rather go back to the room where I recruited you? We might just be able to manage it.”

Through the walls of the cage and shaft I could hear the sirens going full blast, underlining her words.

I shook my head. I said, “I think I knew that—I mean, that I was joining an organization—when I answered your first question.”

“It’s a very big organization,” she went on, as if warning me. “Call it an empire or a power if you like. So far as you are concerned, it has always existed and always will exist. It has agents everywhere, literally. Space and time are no barriers to it. Its purpose, so far as you will ever be able to know it, is to change, for its own aggrandizement, not only the present and future, but also the past. It is a ruthlessly competitive organization and is merciless to its employees.”

“I. G. Farben?” I asked, grabbing nervously and clumsily at humor.

She didn’t rebuke my flippancy, but said, “And it isn’t the Communist Party or the Ku Klux Klan, or the Avenging Angels or the Black Hand, either, though its enemies give it a nastier name.”

“Which is?” I asked.

“The Spiders,” she said.

That word gave me the shudders, coming so suddenly. I expected the sigil to step off her forehead and scuttle down her face and leap at me—something like that.

She watched me. “You might call it the Double Cross,” she suggested, “if that seems better.”

“Well, at least you don’t try to prettify your organization,” was all that I could think to say.

She shook her head. “With the really big ones you don’t have to. You never know if the side into which you are born or reborn is ‘right’ or ‘good’—you only know that it’s your side and you try to learn about it and form an opinion as you live and serve.”

“You talk about sides,” I said. “Is there another?”

“We won’t go into that now,” she said, “but if you ever meet someone with an S on his forehead, he’s not a friend, no matter what else he may be to you. That S stands for Snakes.”

I don’t know why that word, coming just then, gave me so much worse a scare—crystalized all my fears, as it were—but it did. Maybe it was only some little thing, like Snakes meaning DTs. Whatever it was, I felt myself turning to mush.

“Maybe we’d better go back to the room where you found me,” I heard myself saying. I don’t think I meant it, though I surely felt it. The sirens had stopped, but I could hear a lot of general hubbub, outside the hotel and inside it too, I thought—noise from the other elevator shaft and, it seemed to me, from the floor we’d just left—hurrying footsteps, taut voices, something being dragged. I knew terror here, in this stalled elevator, but that loudness outside would be worse.

“It’s too late now,” my conductress informed me. “You see, Buster,” she said, “you’re still back in that room. You might be able to handle the problem of rejoining yourself if you went back alone, but not with other people around.”

“What did you do to me?” I said very softly.

“I’m a Resurrectionist,” she said as quietly. “I dig bodies out of the space-time continuum and give them the freedom of the fourth dimension. When I Resurrected you, I cut you out of your lifeline close to the point that you think of as the Now.”

“My lifeline?” I interrupted. “Something in my palm?”

“All of you from your birth to your death,” she said. “A you-shaped robe embedded in the space-time continuum—I cut you out of it. Or I made a fork in your lifeline, if you want to think of it that way, and you’re in the free branch. But the other you, the buried you, the one people think of as the real you, is back in your room with the other Zombies going through the motions.”

“But how can you cut people out of their lifelines?” I asked. “As a bull-session theory, perhaps. But to actually do it—”

“You can if you have the proper tool,” she said flatly, swinging her handbag. “Any number of agents might have done it. A Snake might have done it as easily as a Spider. Might still—but we won’t go into that.”

“But if you’ve cut me out of my lifeline,” I said, “and given me the freedom of the fourth dimension, why are we in the same old space-time? That is, if this elevator is—”

“It is,” she assured me. “We’re still in the same space-time because I haven’t led us out of it. We’re moving through it at the same temporal speed as the you we left behind, keeping pace with his Now. But we both have an added mode of freedom, at present imperceptible and inoperative. Don’t worry. I’ll make a door and get us out of here soon enough—if you pass the test.”

I stopped trying to understand her metaphysics. Maybe I was between floors with a maniac. Maybe I was a maniac myself. No matter—I would just go on clinging to what felt like reality. “Look,” I said, “that person I murdered, or left to die, is he back in the room too? Did you see him—or her?”

She looked at me and then nodded. She said carefully, “The person you killed or doomed is still in the room.”

An aching impulse twisted me a little. “Maybe I should try to go back––” I began. “Try to go back and unite the selves . . .”

“It’s too late now,” she repeated.

“But I want to,” I persisted. “There’s something pulling at me, like a chain hooked to my chest.”

She smiled unpleasantly. “Of course there is,” she said. “It’s the vampire in you—the same thing that drew me to your room or would draw any Spider or Snake. The blood scent of the person you killed or doomed.”

I drew back from her. “Why do you keep saying ‘or’?” I blustered. “I didn’t look but you must have seen. You must know. Whom did I kill? And what is the Zombie me doing back there in that room with the body?”

“There’s no time for that now,” she said, spreading the mouth of her handbag. “Later you can go back and find out, if you pass the test.”

She drew from her handbag a pale gray gleaming implement that looked by quick turns to me like a knife, a gun, a slim scepter, and a delicate branding iron—especially when its tip sprouted an eight-limbed star of silver wire.

“The test?” I faltered, staring at the thing.

“Yes, to determine whether you can live in the fourth dimension or only die in it.”

The star began to spin, slowly at first, then faster and faster. Then it held still, but something that was part of it or created by it went on spinning like a Helmholtz color wheel—a fugitive, flashing rainbow spiral. It looked like the brain’s own circular scanning pattern become visible and that frightened me because that is what you see at the onset of alcoholic hallucinations.

“Close your eyes,” she said.

I wanted to jerk away, I wanted to lunge at her, but I didn’t dare. Something might shake loose in my brain if I did. The spiral flashed through the wiry fringe of my eyebrows as she moved it closer. I closed my eyes.

Something stung my forehead icily, like ether, and I instantly felt that I was moving forward with an easy rise and fall, as if I were riding a very gentle roller-coaster. There was a low pulsing roar in my ears.

I snapped my eyes open. The illusion vanished. I was standing stock still in the elevator and the only sounds were the continuing hubbub that had succeeded the sirens. My conductress was smiling at me, encouragingly.

I closed my eyes again. Instantly I was surging forward through the dark on the gentle roller-coaster and the hubbub was an almost musical roar that rose and fell. Smoky lights showed ahead. I glided through a cobblestoned alleyway where cloaked and broad-hatted bravoes with rapiers swinging at their sides turned their heads to stare at me knowingly, while women in gaudy dresses that swept the dirt leered in a way that was half inviting, half contemptuous. Darkness swallowed them. An iron gate clanged behind me. Bluer, cleaner lights sprang up. I passed a field studded with tall silver ships. Tall, slender-limbed men and women in blue and silver smocks broke off their tasks or games to watch me—evenly but a little sadly, I thought. They drifted out of sight behind me and another gate clanged. For a moment the pulsing sound shaped itself into words: “There’s a road to travel. It’s a road that’s wide . . .”

I opened my eyes again. I was back in the stalled elevator, hearing the muted hubbub, facing my smiling conductress. It was very strange—an illusion that could be turned on or off by lowering or raising the eyelids. I remembered fleetingly that the brain’s alpha rhythm, which may be the rhythm of its scanning pattern idling, vanishes when you open your eyes and I wondered if the roller-coaster was the alpha rhythm.

When I closed my eyes this time I plunged deeper into the illusion. I burst through many scenes: a street of flashing swords, the central aisle of a dark cavernous factory filled with unknown untended machines, a Chinese pavilion, a Harlem nightclub, a square filled with brightly painted statues and noisy white-togaed men, a humped road across which a ragged muddy-footed throng fled in terror from a porticoed temple which showed only as wide bars of light rising in a mist from behind a low hill.

And always the half-music pulsed without cease. From time to time I heard the “Road to Travel” song repeated with two endings, now one, now another: “It leads around the cosmos to the other side,” and “It leads to insanity or suicide.”

I could have whichever ending I chose, it seemed to me—I needed only will it.

And then it burst on me that I could go wherever I wanted, see whatever I wanted, just by willing it. I was traveling along that dark mysterious avenue, swaying and undulating in every dimension of freedom, that leads to every hidden vista of the unconscious mind, to any and every spot in space and time—the avenue of the adventurer freed from all limitations.

I grudgingly opened my eyes again to the stalled elevator. “This is the test?” I asked my conductress quickly. She nodded, watching me speculatively, no longer smiling. I dove eagerly back into the darkness.

In the exultation of my newly realized power I skimmed a universe of sensation, darting like a bird or bee from scene to scene, a battle, a banquet, a pyramid a-building, a tatter-sailed ship in a storm, beasts of all descriptions, a torture chamber, a death ward, a dance, an orgy, a leprosary, a satellite launching, a stop at a dead star between galaxies, a newly-created android rising from a silver vat, a witch-burning, a cave birth, a crucifixion . . .

Suddenly, I was afraid. I had gone so far, seen so much, so many gates had clanged behind me, and there was no sign of my free flight stopping or even slowing down. I could control where I went, but not whether I went––I had to keep on going. And going. And going.

My mind was tired. When your mind is tired and you want to sleep you close your eyes. But if, whenever you close your eyes, you start going again, you start traveling the road . . .

I opened mine. “How do I ever sleep?” I asked the woman. My voice had gone hoarse.

She didn’t answer. Her expression told me nothing. Suddenly I was very frightened. But at the same time I was horribly tired, mind and body. I closed my eyes…

I was standing on a narrow ledge that gritted under the soles of my shoes whenever I inched a step one way or another to ease the cramps in my leg muscles. My hands and the back of my head were flattened against a gritty wall. Sweat stung my eyes and trickled inside my collar. There was a medley of voices I was trying not to hear. Voices far below.

I looked down at the toes of my shoes, which jutted out a little over the edge of the ledge. The brown leather was dusty and dull. I studied each gash in it, each rolled or loose peeling of tanned surface, each pale shallow pit.

Around the toes of my shoes a crowd of people clustered, but small, very small––tiny oval faces mounted crosswise on oval bodies that were scarcely larger—navy beans each mounted on a kidney bean. Among them were red and black rectangles, proportionately small—police cars and fire trucks. Between the toes of my shoes was an empty gray space.

In spirit or actuality, I was back in the body I had left in the hotel bedroom, the body that had climbed through the window and was threatening to jump.

I could see from the corner of my eye that someone in black was standing beside me, in spirit or actuality. I tried to turn my head and see who it was, but that instant the invisible roller-coaster seized me and I surged forward and—this time—down.

The faces started to swell. Slowly.

A great scream puffed up at me from them. I tried to ride it but it wouldn’t hold me. I plunged on down, face first.

The faces below continued to swell. Faster. Much faster, and then . . .

One of them looked all matted hair except for the forehead, which had an S on it.

My fall took me past that horror face and then checked three feet from the gray pavement (I could see fine, dust-drifted cracks and a trodden wad of chewing gum) and without pause I shot upward again, like a high diver who fetches bottom, or as if I’d hit an invisible sponge-rubber cushion yards thick.

I soared upward in a great curve, losing speed all the time, and landed without a jar on the ledge from which I’d just fallen.

Beside me stood the woman in black. A gust of wind ruffled her bangs and I saw the eight-limbed sigil on her forehead.

I felt a surge of desire and I put my arms around her and pulled her face toward mine.

She smiled but she dipped her head so that our foreheads touched instead of our lips.

Ether ice shocked my brain. I closed my eyes for an instant.

When I opened them we were back in the stalled elevator and she was drawing away from me with a smile and I felt a wonderful strength and freshness and power, as if all avenues were open to me now without compulsion, as if all space and time were my private preserve.

I closed my eyes and there was only blackness quiet as the grave and close as a caress. No roller-coaster, no scanning pattern digging movement and faces from the dark, no realms of the DT fringes. I laughed and I opened my eyes.

My conductress was at the controls of the elevator and we were dropping smoothly and her smile was sardonic but comradely now, as if we were fellow professionals.

The elevator stopped and the door slid open on the crowded lobby and we stepped out arm in arm. My partner checked a moment in her stride and I saw her lift an “Out of Order” sign off the door and drop it behind the sand vase.

We strode toward the entrance. I knew what Zombies were now—the people around me, hotel folk, public, cops, firemen. They were all staring toward the entrance, where the revolving doors were pinned open, as if they were waiting (an eternity, if necessary) for something to happen. They didn’t see us at all—except that one or two trembled uneasily, like folk touched by nightmares, as we brushed past them.

As we went through the doorway my partner said to me rapidly, “When we get outside do whatever you have to, but when I touch your shoulder come with me. There’ll be a Door behind you.”

Once more she drew the gray implement from her handbag and there was a silver spinning behind me. I did not look at it.

I walked out into empty sidewalk and a scream that came from dozens of throats. Hot sunlight struck my face. We were the only souls for ten yards around, then came a line of policemen and the screaming mob. Everyone of them was looking straight up, except for a man in dirty shirtsleeves who was pushing his way, head down, between two cops.

You know the sound when a butcher slams a chunk of beef down on the chopping block? I heard that now, only much bigger. I blinked my eyes and there was a body on its back in the middle of the empty space and the finest spray of blood was misting down on the gray sidewalk.

I sprang forward and knelt beside the body, vaguely aware that the man who had pushed between the cops was doing the same from the other side. I studied the face of the man who had leaped to his death.

The face was unmarred, though it was rather closer to the sidewalk than it would have been if the back of the head had been intact. It was a face with a week’s beard on it that rose higher than the cheekbones—the big forehead was the only sizeable space on it clear of hair. It was the tormented face of a drunk, but now at peace. It was a face I knew, in fact had always known. It was simply the face my conductress had not let me see, the face of the person I had doomed to die: myself.

I lifted my hand and this time I let it touch the week’s growth of beard matting my face.

Well, I thought, I had given the crowd an exciting half hour.

I lifted my eyes and there on the other side of the body was the dirty-sleeved man. It was the same beard-matted face as that on the ground between us, the same beard-matted face as my own.

On the forehead was a black S that looked permanent.

He was staring at my face—and then at my forehead—with a surprise, and then a horror, that I knew my own features were registering too as I stared at him. A hand touched my shoulder.

My conductress had told me that you never know whether the side into which you are born or reborn is “right” or “good.” Now, as I turned and saw the shimmering silver man-high Door behind me, and her hand vanishing into it, and as I stepped through, past a rim of velvet blackness and stars, I clung to that memory, for I knew that I would be fighting on both sides forever.

Fritz Leiber

Neil Gaiman on The Big Time

Read Biography

Fritz Leiber—The Big Time: An Introduction

Fritz Leiber remembers how he came to write The Big Time in this introduction to the novel, added to a new edition in 1982.Foreword to The Mind Spider and Other Stories

Fritz Leiber Bonus Material

Here are three 1950s radio adaptations of Leiber's stories from the NBC radio program X Minus One plus five Change War stories exploring the war between Spiders and Snakes in The Big Time.Other Novels by Fritz Leiber