Try and Change the Past

Astounding Science Fiction, March 1958

No, I wouldn’t advise anyone to try to change the past, at least not his personal past, although changing the general past is my business, my fighting business. You see, I’m a Snake in the Change War. Don’t back off––human beings, even Resurrected ones engaged in time-fighting, aren’t built for outward wriggling and their poison is mostly psychological. “Snake” is slang for the soldiers on our side, like Hun or Reb or Ghibbelin. In the Change War we’re trying to alter the past––and it’s tricky, brutal work, believe me—at points all over the cosmos, anywhere and anywhen, so that history will be warped to make our side defeat the Spiders. But that’s a much bigger story, the biggest in fact, and I’ll leave it occupying several planets of microfilm and two asteroids of coded molecules in the files of the High Command.

Change one event in the past and you get a brand new future? Erase the conquests of Alexander by nudging a neolithic pebble? Extirpate America by pulling up a shoot of Sumerian grain? Brother, that isn’t the way it works at all! The space-time continuum’s built of stubborn stuff and change is anything but a chain-reaction. Change the past and you start a wave of changes moving futurewards, but it damps out mighty fast. Haven’t you ever heard of temporal reluctance, or of the Law of the Conservation of Reality?

Here’s a little story that will illustrate my point: This guy was fresh recruited, the Resurrection sweat still wet in his armpits, when he got the idea he’d use the time-traveling power to go back and make a couple of little changes in his past so that his life would take a happier course and maybe, he thought, he wouldn’t have to die and get mixed up with Snakes and Spiders at all. It was as if a new-enlisted feuding hillbilly soldier should light out with the high-power rifle they issued him to go back to his mountains and pick off his pet enemies.

Normally it couldn’t ever have happened. Normally, to avoid just this sort of thing, he’d have been shipped straight off to some place a few thousand or million years distant from his point of enlistment and maybe a few light-years, too. But there was a local crisis in the Change War and a lot of routine operations got held up and one new recruit was simply forgotten.

Normally, too, he’d never have been left alone a moment in the Dispatching Room, never even have glimpsed the place except to be rushed through it on arrival and reshipment. But, as I say, there happened to be a crisis, the Snakes were shorthanded, and several soldiers were careless. Afterwards two N.C.’s were busted because of what happened and a First Looey not only lost his commission but was transferred outside the galaxy and the era. But during the crisis this recruit I’m telling you about had opportunity and more to fool around with forbidden things and try out one of his schemes.

He also had all the details on the last part of his life back in the real world, on his death and its consequences, to mull over and be tempted to change. This wasn’t anybody’s carelessness. The Snakes give every candidate that information as part of the recruiting pitch. They spot a death coming and the Resurrection Men go back and recruit the person from a point a few minutes or at most a few hours earlier. They explain in uncomfortable detail what’s going to happen and wouldn’t he rather take the oath and put on scales? I never heard of anybody turning down that offer. Then they lift him from his lifeline in the form of a Doubleganger and from then on, brother, he’s a Snake.

So this guy had a clearer picture of his death than of the day he bought his first car, and a masterpiece of morbid irony it was. He was living in a classy penthouse that had belonged to a crazy uncle of his––it even had a midget astronomical observatory, unused for years––but he was stony broke, up to the top hair in debt, and due to be dispossessed next day. He’d never had a real job, always lived off his rich relatives and his wife’s, but now he was getting a little too mature for his stern dedication to a life of sponging to be cute. His charming personality, which had been his only asset, was deader from overuse and abuse than he himself would be in a few hours. His crazy uncle would not have anything to do with him any more. His wife was responsible for a lot of the wear and tear on his social-butterfly wings; she had hated him for years, had screamed at him morning to night the way you can only get away with in a penthouse, and was going batty herself. He’d been playing around with another woman, who’d just given him the gate, though he knew his wife would never believe that and would only add a scornful note to her screaming if she did.

It was a lousy evening, smack in the middle of an August heat wave. The Giants were playing a night game with Brooklyn. Two long-run musicals had closed. Wheat had hit a new high. There was a brush fire in California and a war scare in Iran. And tonight a meteor shower was due, according to an astronomical bulletin that had arrived in the morning mail addressed to his uncle—he generally dumped such stuff in the fireplace unopened, but today he had looked at it because he had nothing else to do, either more useful or more interesting.

The phone rang. It was a lawyer. His crazy uncle was dead and in the will there wasn’t a word about an Asteroid Search Foundation. Every penny of the fortune went to the no-good nephew.

This same character finally hung up the phone, fighting a tendency for his heart to spring giddily out of his chest and through the ceiling. Just then his wife came screeching out of the bedroom. She’d received a cute, commiserating, tell-all note from the other woman; she had a gun and announced that she was going to finish him off.

The sweltering atmosphere provided a good background for sardonic catastrophe. The French doors to the roof were open behind him but the air that drifted through was muggy as death. Unnoticed, a couple of meteors streaked faintly across the night sky.

Figuring it would sure dissuade her, he told her about the inheritance. She screamed that he’d just use the money to buy more other women—not an unreasonable prediction––and pulled the trigger.

The danger was minimal. She was at the other end of a big living room, her hand wasn’t just shaking, she was waving the nickel-plated revolver as if it were a fan.

The bullet took him right between the eyes. He flopped down, deader than his hopes were before he got the phone call. He saw it happen because as a clincher the Resurrection Men brought him forward as a Doubleganger to witness it invisibly—also standard Snake procedure and not productive of time-complications, incidentally, since Doublegangers don’t imprint on reality unless they want to.

They stuck around a bit. His wife looked at the body for a couple of seconds, went to her bedroom, blonded her graying hair by dousing it with two bottles of undiluted peroxide, put on a tarnished gold-lamé evening gown and a bucket of make-up, went back to the living room, sat down at the piano, played “Country Gardens” and then shot herself, too.

So that was the little skit, the little double blackout, he had to mull over outside the empty and unguarded Dispatching Room, quite forgotten by its twice-depleted skeleton crew while every available Snake in the sector was helping deal with the local crisis, which centered around the planet Alpha Centauri Four, two million years minus.

Naturally it didn’t take him long to figure out that if he went back and gimmicked things so that the first blackout didn’t occur, but the second still did, he would be sitting pretty back in the real world and able to devote his inheritance to fulfilling his wife’s prediction and other pastimes. He didn’t know much about Doublegangers yet and had it figured out that if he didn’t die in the real world he’d have no trouble resuming his existence there—maybe it’d even happen automatically.

So this Snake––name kind of fits him, doesn’t it?––crossed his fingers and slipped into the Dispatching Room. Dispatching is so simple a child could learn it in five minutes from studying the board. He went back to a point a couple of hours before the tragedy, carefully avoiding the spot where the Resurrection Men had lifted him from his lifeline. He found the revolver in a dresser drawer, unloaded it, checked to make sure there weren’t any more cartridges lying around, and then went ahead a couple of hours, arriving just in time to see himself get the slug between the eyes same as before.

As soon as he got over his disappointment, he’d learned something about Doublegangers he should have known all along, if his mind had been clicking. The bullets he’d lifted were Doublegangers, too; they had disappeared from the real world only at the point in space-time where he’d lifted them, and they had continued to exist, as real as ever, in the earlier and later sections of their lifelines—with the result that the gun was loaded again by the time his wife had grabbed it up.

So this time he set the board so he’d arrive just a few minutes before the tragedy. He lifted the gun, bullets and all, and waited around to make sure it stayed lifted. He figured––rightly—that if he left this space-time sector the gun would reappear in the dresser drawer, and he didn’t want his wife getting hold of any gun, even one with a broken lifeline. Afterwards—after his own death was averted, that is—he figured he’d put the gun back in his wife’s hand.

Two things reassured him a lot, although he’d been expecting the one and hoping for the other: his wife didn’t notice his presence as a Doubleganger and when she went to grab the gun she acted as if it weren’t gone and held her right hand just as if there were a gun in it. If he’d studied philosophy, he’d have realized that he was witnessing a proof of Leibniz’s theory of Pre-established harmony: that neither atoms nor human beings really affect each other, they just look as if they did.

But anyway he had no time for theories. Still holding the gun, he drifted out into the living room to get a box seat right next to Himself for the big act. Himself didn’t notice him any more than his wife had.

His wife came out and spoke her piece same as ever. Himself cringed as if she still had the gun and started to babble about the inheritance, his wife sneered and made as if she were shooting Himself.

Sure enough, there was no shot this time, and no mysteriously appearing bullet hole—which was something he’d been afraid of. Himself just stood there dully while his wife made as if she were looking down at a dead body and went back to her bedroom.

He was pretty pleased: this time he actually had changed the past. Then Himself slowly glanced around at him, still with that dull look, and slowly came toward him. He was more pleased than ever because he figured now they’d melt together into one man and one lifeline again, and he’d be able to hurry out somewhere and establish an alibi, just to be on the safe side, while his wife suicided.

But it didn’t happen quite that way. Himself’s look changed from dull to desperate, he came up close… and suddenly grabbed the gun and quick as a wink put a thumb to the trigger and shot himself between the eyes. And flopped, same as ever.

Right there he was starting to learn a little—and it was an unpleasant and shivery sort of learning—about the Law of the Conservation of Reality. The four-dimensional space-time universe doesn’t like to be changed, any more than it likes to lose or gain energy or matter. If it has to be changed, it’ll adjust itself just enough to accept that change and no more. The Conservation of Reality is a sort of Law of Least Action, too. It doesn’t matter how improbable the events involved in the adjustment are, just so long as they’re possible at all and can be used to patch the established pattern. His death, at this point, was part of the established pattern. If he lived on instead of dying, billions of other compensatory changes would have to be made, covering many years, perhaps centuries, before the old pattern could be re-established, the snarled lifelines woven back into it––and the universe finally go on the same as if his wife had shot him on schedule.

This way the pattern was hardly effected at all. There were powder burns on his forehead that weren’t there before, but there weren’t any witnesses to the shooting in the first place, so the presence or absence of powder burns didn’t matter. The gun was lying on the floor instead of being in his wife’s hands, but he had the feeling that when the time came for her to die, she’d wake enough from the Pre-established Harmony trance to find it, just as Himself did.

So he’d learned a little about the Conservation of Reality. He also had learned a little about his own character, especially from Himself’s last look and act. He’d got a hint that he had been trying to destroy himself for years by the way he’d lived, so that inherited fortune or accidental success couldn’t save him, and if his wife hadn’t shot him he’d have done it himself in any case. He’d got a hint that Himself hadn’t merely been acting as an agent for a self-correcting universe when he grabbed the gun, he’d been acting on his own account, too—the universe, you know, operates by getting people to co-operate.

But, although these ideas occurred to him, he didn’t dwell on them, for he figured he’d had a partial success the second time, and the third time if he kept the gun away from Himself, if he dominated Himself, as it were, the melting-together would take place and everything else would go forward as planned.

He had the dim realization that the universe, like a huge sleepy animal, knew what he was trying to do and was trying to thwart him. This feeling of opposition made him determined to outmaneuver the universe—not the first guy to yield to such a temptation, of course.

And up to a point his tactics worked. The third time he gimmicked the past, everything started to happen just as it did the second time. Himself dragged miserably over to him, looking for the gun, but he had it tucked away and was prepared to hold onto it. Encouragingly, Himself didn’t grapple, the look of desperation changed to one of utter hopelessness, and Himself turned away from him and very slowly walked to the French doors and stood looking out into the sweating night. He figured Himself was just getting used to the idea of not dying. There wasn’t a breath of air. A couple of meteors streaked across the sky. Then, mixed with the up-seeping night sounds of the city, there was a low whirring whistle.

Himself shook a bit, as if he’d had a sudden chill. Then Himself turned around and slumped to the floor in one movement. Between his eyes was a black hole.

Then and there this Snake I’m telling you about decided never again to try and change the past, as least not his personal past. He’d had it, and he’d also acquired a healthy respect for a High Command able to change the past, albeit with difficulty. He scooted back to the Dispatching Room, where a sleepy and surprised Snake gave him a terrific chewing-out and confined him to quarters. The chewing-out didn’t bother him too much—he’d acquired a certain fatalism about things. A person’s got to learn to accept reality as it is, you know––just as you’d best not be surprised at the way I disappear in a moment or two—I’m a Snake too, remember.

If a statistician is looking for an example of a highly improbable event, he can hardly pick a more vivid one than the chance of a man being hit by a meteorite. And, if he adds the condition that the meteorite hit him between the eyes so as to counterfeit the wound made by a 32-caliber bullet, the improbability becomes astronomical cubed. So how’s a person going to outmaneuver a universe that finds it easier to drill a man through the head that way rather than postpone the date of his death?

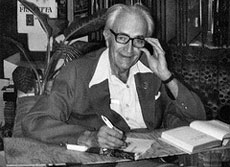

Fritz Leiber

Neil Gaiman on The Big Time

Read Biography

Fritz Leiber—The Big Time: An Introduction

Fritz Leiber remembers how he came to write The Big Time in this introduction to the novel, added to a new edition in 1982.Foreword to The Mind Spider and Other Stories

Fritz Leiber Bonus Material

Here are three 1950s radio adaptations of Leiber's stories from the NBC radio program X Minus One plus five Change War stories exploring the war between Spiders and Snakes in The Big Time.Other Novels by Fritz Leiber